When I heard that my old friend Rod Humble was making a game about the spread of religions, I knew I was going to be playing it. Rod has always had an interesting approach to game design, almost more interested in posing questions (whether about history or emotional connection in games) and I had high hopes that Cults and Daggers would be the same sort of mind-twisting, self-reflective sort of game that I came to expect from him.

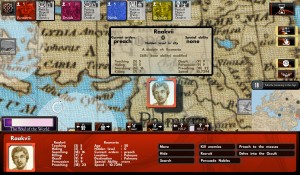

Of course, when you’re selling a game on Steam for 30 dollars, there are limits to how “out there” you can go, and Cults and Daggers is ultimately a quite conventional territory control game that uses persuasion and secrecy instead of armies. It’s underdocumented (I’m not sure exactly what wars do, or what happens to the map between ages) and the UI is a mess. But it does have interesting ideas, and a quite old-fashioned style of play. Some people have been able to use its thin religious veneer to reconnect with their personal ideas of faith. I was never able to make that leap.

It’s probably not surprising that I couldn’t quite connect with it. Religion in games is generally a matter of special buffs or general harmony. In Civilization IV, a multifaith empire that controlled all the Holy Cities was an unstoppable force of culture and gold. In Civilization V, you pick generic religious “beliefs” if you found a new faith, but the most powerful ones are, again, related to bringing in gold or special buildings. Our games at Paradox (the Crusader Kings and Europa Universalis series) give every religion an attribute or two that, usually, give you bonuses or new game experiences.

But Dominions is about becoming a god, not founding a religion. The temple in Rise of Nations expands your boundaries and increases tax income, but is not a building of “faith”.

So the more I think on it, the more I think that Cults and Daggers is not about faith at all. It might be about religion, but it’s really about fear.

It’s important to keep in mind that C&D is a quasi-historical game. By that, I mean that it uses a roughly historic setting (in this case, Hellenistic Europe between the death of Buddha and the birth of Christ) but attaches themes and mechanics that stand outside or apart from that historic age. In this historic period, the region was not full of competing religions, each one trying to destroy the other; for the most part, advanced civilizations easily assimilated foreign deities. The recruiting of disciples and driving out of rival sects is, in fact, a phenomenon of the Christian and post-Christian world.

C&D also has an apocalyptic timer, something that would have been alien to most religions and cults of the era. The only really historical thing in C&D is the map and its 12 cities. The setting is a buy-in, a way to entice people with a familiar script and then give them something weird. Like disciples that turn in monsters or places of power that send bad juju to neighboring cities if they aren’t cleansed by a holy man or woman.

The general theme of C&D is, in fact, that everyone is out to destroy you and your community of believers unless you can get to them first. You can blaspheme against local gods and then pin the blame on a rival cult. You can go into deep cover, only emerging to murder a persuasive enemy preacher. You can invoke prayers that will transform your ministers into agents of chaos. You build temples, suck up to nobles for protection and count on the hope of the people to carry you into the next age.

In many ways, it is a very paranoid game. Naturally, any game that has Old Gods in it gives you a reason to be paranoid. You accumulate hope and faith (and occult power) not just to fill the coffers of your church, but to stave off the end of days.

This is, of course, one theory of the origins of religion made manifest. Some anthropologists argue that priests came about in early societies because that rituals were required to hold off community disaster. Even advanced religions fell into a sort of ritual paranoia; the Romans were so antsy about this sort of thing that if some rituals were interrupted, they had to be performed again from the beginning, or invite calamity.

The religions you promote in C&D are content-free, just like those of most religions in strategy games. You pick a perk at the beginning and add more “prayers” as you go through the game, but these, again, are bonuses to disciple power, faith, hope, etc. The mere fact of believing in something is what is holding off the world-ending apocalypse, but you are engaged in a death struggle with other cults to make sure your religion comes out on top. To stay number one with the people, you will need to spend the hope and faith that you also need to keep evil at bay. And nothing is certain, and disciples grow old and die, and it is a long way from Carthage to Babylon.

I do like that Cults and Daggers doesn’t cast you as a demigod, like in Dominions, or a Devil, like in Solium Infernum (which is either the most blasphemous or more Christian strategy game ever made). And strategy games, with their emphasis on systems and patterns instead of story will never give us a living, breathing faith as powerful as the Chantry in the Dragon Age series.

But if you want to play a simple game where you are a small collection of believers trying to stay alive in a world that distrusts novelty while under attack from imaginable horrors (imaginable, because you don’t see a lot of evil in the game), then there might be something here that connects with you.

I do know I want Rod Humble to keep making weird things like this.

Hey Troy! Thank you for taking the time to write this and to play the game. I do think the sense I got from my reading of the religions of the period is one of fickle paranoia, I didnt really see that until you wrote it.

My one mild disagreement with you might be on the nature of Cults and religious tolerance at the time. I take away a rather darker reading from the texts, where Cults attacked each other (for example the attacks on the Pythagorean cult) and religious wealth manipulating actions (the influence of the Temple of Apollo for example) being an accepted fact of life.

You are correct of course about the doomsday scenario. This is a story I invented to fill in the gaps about what the Mystery Cults were actually up to. It is a delightful/frustrating thing, we had the flourishing of many such cults during this time but they kept their secrets well, leaving us able to invent as we like. I chose this sense of evil trying to destroy the world in between Buddha and Christ.

Anyway, it looks like you were perhaps not grabbed by the game, but I appreciate your writing about it. I will indeed keep making unusual personal games, promise me you will keep writing interesting thoughts!

I appreciate your kind words!

Best

Rod

Hey Rod.

There was certainly paranoia about some specific cults – Roman fear of the Mystery Cults and the Pythagoreans you cite are the most famous. But these were seen as destablizing, and they are outliers in a larger more welcoming world space. Alexander’s offerings to Osiris, the Ptolemaic merger of Hellenistic and Egyptian faiths, the Isis and Mitraic cults in Rome.

Really, the Jews are the odd ones out, fighting against any foreign intrusion into their sacred cities. But they also never went converting. Pre-Christian/Muslim evangelism is a hard mental space to get into, but a lot of games struggle with this.

My feelings about C&D are certainly not entirely negative. And I hope you revisit this topic again. There is _something_ of great value here.